I

spent the early afternoon today shopping for antiques on Shanghai's

Fangbangzhong Lu. One has to dig around, but there are still good things

to be found here. In particular one stumbles across numerous fine

Buddhist artifacts that ought to be rescued from the obscurity thrust

upon them by time, disinterest, and communism. At times it looks to me

like the whole religion is up for sale here.

On the other hand, a

quick perusal of the rafters of ads in Shambala magazine gives much the

same impression. I sometimes ask myself, why does every impulse in man

ultimately turn up as merchandise?

I got back to the hotel

drenched in sweat -- I gave myself the task of lugging heavy stone

Buddhas by foot through the streets to get some exercise -- and had a

fine sandwich in the lobby. Now I sit on the 39th floor of an ultra

modern skyscraper staring across a city that is suddenly drenched in

mist and rain, and intermittently thrashed by spectacular bolts of

lightning.

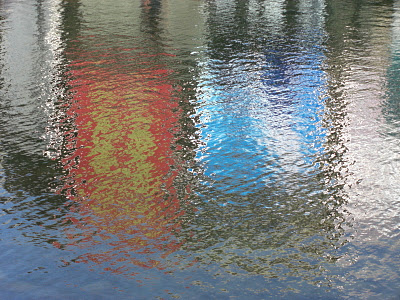

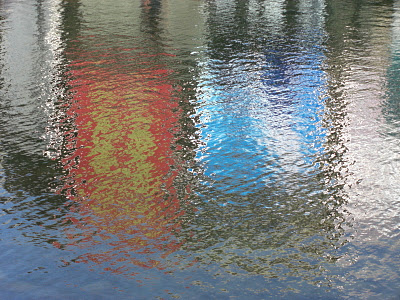

Even the most contemporary architecture assumes a

primeval aspect when it is surrounded and softened by the medium of

water, and then highlighted with intense jolts of natural electricity. I

could offer you a picture this very instant of the exact impression

before me, but the picture I took yesterday -- reflections of

advertising signs in a pond in the Ningbo -- is so appealing abstract

and colorful that I prefer it.

Let's move on to the subject of the day.

Those

who read my posts regularly are aware that I have been engaged for a

number of years now in the study of inner negativity--what it is, why it

arises, and how we can become less subject to it.

As I continue,

on this trip, to review Gurdjieff's "Beelzebub"--part of an audio

project whose results will be completed and released,

insh'Allah,

in the eventual future--I am still engaged in the final chapter, "from

the author." One of the signature features of the lecture presented in

this chapter is the discussion of the famous traditional yoga analogy of

man's inner organization to a horse, a driver, and a carriage.

Astute

readers of this passage may pick up on the fact that in Gurdjieff's

eyes, the part of the arrangement that has the most serious problems is

the horse -- that is, the emotions. The driver functions at least

marginally, and the carriage may be challenged, but it is at least

functional. The emotions,on the other hand, have been completely abused

and are all but uneducated.

I believe we need to study this

question in much more detail. As I have indicated before, the health

and well-being of the emotional center depends on the interrelationship

between the organs-- the inner flowers--that conduct its vibrations.

Without a healthy emotional center, the motive force of our inner work

is crippled.

It's clear that this emotional deficit is a

universal problem: half the nation is on prescription mood enhancers of

one kind or another. When a significant portion of the population needs

drugs to feel emotionally whole, it's clear something is going very

wrong inside people. What's even more surprising, we don't even question

it. In this day and age, it is just about taken for granted that our

emotions are going to be broken.

How many of us, however, sit

down every morning to conduct, through meditation, a thorough study of

our emotional state in order to determine

why it's broken?

All

the chemicals we are using to boost our morale are chemicals we ought

to be producing on our own. One would think we might want to undertake

an effort in this regard, rather than swallowing little colored pills.

As one of my group members said to me a while back, "the chemicals we

make ourselves are

better."

I

remember that many years ago, when I asked how to approach work on the

emotions, my teacher indicated that there was no way to work directly on

the emotions, that this would enter my work "on its own" when it was

necessary.

I don't like to contradict my own teacher, who I

deeply love and respect. I owe her a great deal. Nonetheless, my own

investigations over the past five years have led me to believe that her

take on this is not correct.

The specific work of receiving and connecting the inner energies

is work

on the emotions. This work needs to be conducted in strict accordance

with the enneagram, a detail that seems lost on many of those who are

familiar with the Gurdjieff work.

It's essentially true that just

about every major branch of yoga understands work with energy, and in

this manner one might say they are all equal, and that the Gurdjieff

work is the "same" work. That, however, is a terribly mistaken point of

view. It would only be true if there were no enneagram. The enneagram

provides the objective organizing principle for inner work with energy

that was lost by all the yoga schools.

Does anyone take it

seriously? Our attitude is usually "oh, yeah, the enneagram." And we

move on to other more important questions. Here I am tempted, like Zen

master Dogen, to castigate the "mistaken views of non-Buddhists."

In order to reorganize, to reconnect and, yes,

remember the

proper work of the emotional center, and to learn how to acquire the

food that is needed for it, we must work according to the principles of

the enneagram. This should not be so mysterious. The cult of avoidance

that seems to have arisen within the formal branches of the Gurdjieff

work in regard to this question needs to be overcome. The diagram is

perhaps the most important tool the school has, and yet I do not see

enough serious work being done on it. In the past 25 years I have

consistently discovered that any potentially practical application of

this diagram is almost completely ignored.

Amazing, isn't it?

All

right. Enough of my incessant preaching about this subject. Let's

talk about the nature of emotion and its place in our work.

Based

on my own observations and research, right emotional food changes the

center of gravity in our lives in a dramatic manner. If and when we

acquire it, several emotional features emerge within a man that are

completely buried and deeply dysfunctional under ordinary circumstances.

The first feature is

gratitude, and the second one is

compassion.

Right

emotional food will bring a profound and penetrating gratitude for even

the most ordinary circumstances of life. This gratitude is organic,

that is, it arises within the marrow of the bones, lives within the

spine, expands the heart, and comes to dominate the experience of life.

It carries within it the seeds of that experience Mr. Gurdjieff called

"remorse of conscience." Those seeds, by the way, are also the seeds of

Joy.

It is possible to feel gratitude towards a pencil, or a

windblown piece of trash. This emotion of gratitude should appear within

the landscape of life on a daily basis; it is a fundamental aspect of

the Dharma. It is absent simply because the parts that produce it are

starved. Let me be clear: we do not need to

seek gratitude. If we are working in a right way, gratitude will seek

us.Compassion

is a larger question. Compassion arises from the interaction between

the emotional center and the added, and blended, experiences of the

intellectual and moving center. In a sense, this feature belongs to the

fourth personality of man. It should always be present. In fact, as

the Buddhists maintained, and as Christ probably would have insisted, it

is man's most important calling.

And once again: if we work in a right way, we will not need to

try to "practice" compassion. We will

be compassionate. Real compassion is effortless; it arises as a natural consequence of right work.

If

we refer to the chapter "From the Author," page 1087 in the new

edition, we find Mr. Gurdjieff saying: "...the highest aim and sense of

human life is the striving for the welfare of one's neighbor," and...

this is attainable only through the conscious renunciation of one's

own."

If this is not a description of compassion, I will eat my

hat. Mr. Gurdjieff was no fringe figure, no mountebank establisher of

unique and deviant cults; the

central question of his work was the question of compassion--as it must be in every real work.

If

a man develops a real "I", compassion will emerge in the same way that

the sun rises in the morning. Love is the heart of this work we are in.

Those

of you who have taken the time to download my essay on chakras and the

enneagram have been introduced to the understanding that the energy we

must feed ourselves with is Love. Love is not an abstraction or concept,

it is an

actual physical food that we are able to receive and ingest.

If

you don't already know this personally, my friends, you deserve to.

Understanding work in this way will utterly change your life.

Mankind

was created for this purpose. It's sad that, taken as a whole, so

little of humanity has any experience of this. If there truly is a

sorrow at the heart of the universe, it would have to be God's sorrow at

seeing what he has made available for his creation-- which we all so

cavalierly ignore and throw away. Jesus tried to remind us of this in

his sermon on the Mount when he referred to the lilies of the field.

In seeking to heal the emotional center, we seek to find in the food of love, to

receive

it within this vessel, to bring the vibrations that it carries into

right relationship within all of the inner parts, so that at least a

trickle of it can enter our daily life.

I remember a moment from

years ago: one of our more venerable movement teachers reading to us at

the end of a class from a text written by the master of the Mevlevi

dervishes.

I'll have to paraphrase.

"People don't understand why we turn," the master said. "We turn in order to

bring down the light. There can be no more beautiful work."

Amen to that, brothers and sisters.

May your trees bear fruit, and your wells yield water.

We

just got back from an upstate wedding... many impressions of rolling

hills, glacial valleys, devonian shales, arts and crafts--the wedding

took place at the Rochester Folk Art Guild-- and many celebratory

people.

We

just got back from an upstate wedding... many impressions of rolling

hills, glacial valleys, devonian shales, arts and crafts--the wedding

took place at the Rochester Folk Art Guild-- and many celebratory

people.