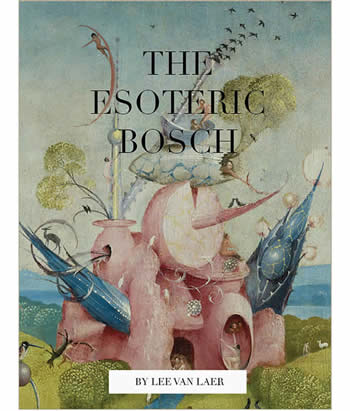

an e-book by Lee van Laer The Esoteric Bosch

After several years of studying Hieronymus Bosch's paintings in order to discern their esoteric content, I'm struck by just how unusual his body of work is. There are few enough consistent bodies of painting with legitimate esoteric content to begin with; painting has always been an expensive activity, largely dependent on patronage or sales by popular appeal in order for materials-let alone that most valuable of commodities, time- to be affordable in the first place. The number of aficionados both willing and wealthy enough to pay for works outside the spiritual and cultural mainstream has always been commensurately small. To find a large body of work, then, which clearly centers around revelatory inner insights (as the Garden of Earthly Delights so amply demonstrates) is highly unusual- in fact, this instance is probably unique, at least in the West. It has always been so recognized, insofar as the work itself displays (as it must) a high degree of originality, idiosyncrasy, and mystique. But the exact nature of Bosch's revelations-and hence the full implications of the content of his paintings- has never been well understood. That the man was different has always been recognized. How and why he was different hasn't been. In trying to set at least some fraction of the record on this great master straight, I have continued a journey that began in 1964 when I was nine years old and stood in front of the Garden, mesmerized, at the Prado in Madrid. Little did I know (as I spent well over an hour gazing at the painting, a matter that has become something of a family legend) that that journey would span, until now, nearly fifty years- years which took me all over the world, and initiated me into Christian, Buddhist, and Sufi mysticism through the auspices of the Gurdjieff work, where I met Elizabeth Brown. Teal, as her friends called her, selflessly took on responsibility for my inner development when I was an eager, unformed, and arrogant young man. Against all odds, my journey included a personal divine revelation, without which my insight into Bosch's work would not have been possible; and, as the artist's work itself reminds us, nothing arises except through Grace alone. Then again, of course, this story is not about me, but rather the extraordinary legacy Bosch left us, and the timeless ideas he encoded in his work for future generations to appreciate. Unlike so much of western art, where paintings are individual masterpieces, unconnected except by the artist's style or a general choice of subject matter, Bosch gave us a body of work that represents a whole — it is a unified body of material, unified not so much by the style or individual images as by the philosophical and religious insights that bind his pieces together. The artist created a consistent language which he used from painting to painting — unusual in itself. The language was not a subjective language, peculiar only to the artist himself, but a language which touched on universal principles over and over again, embodying them in a series of contexts that progressively enrich one another as they develop. As such, Bosch's esoteric paintings ought not be viewed as individual works, but rather as components of a single extensive dialogue, a visual novel, if you will, about the development of man's inner possibilities. Like all great masters, he inseminated his times with a divine energy and founded a school; unlike priests, monks, or other mystics, however, he founded a visual school, based on the art of symbolic painting. Bosch's art represents the final and greatest flowering of the Medieval tradition of mystical and revelatory religious symbolism, which was effectively exterminated in a few generations by the increasingly secular literalism of the Renaissance. The Renaissance has consistently (and mistakenly) been viewed as a progressive and positive development by art historians, rather than the degenerative lowering of inner understanding which it actually represents. The fact that the Northern esoteric schools produced the most enduring artworks of the Middle Ages, including all the great Gothic cathedrals, shows us that the inner traditions were at their deepest and most widespread there, rather than in Italy and the other Mediterranean countries. Thus it's no surprise that the Northern Renaissance so greatly surpassed the southern, especially in regard to the quality and content of the painting; or that Bosch was Flemish instead of Florentine. Like all schools, after Bosch died, the teaching quickly dissipated, losing its force-the predictable fate of all such enterprises, exactly as Gurdjieff explained to Ouspensky in In Search of the Miraculous. His imitators did, to be sure, work with similar images, but all of them were employed mechanically, without any understanding of the subtle relationships that Bosch used in order to illustrate esoteric truth. As such, they became as codified as the ritualistic liturgies of the Orthodox church; and in that form, they have endured to the present day, inspiring countless conceptual visions of heaven and hell. In an equally lawful manner, they have spawned much confusion and argument; few people obtain the kind of insights Bosch enjoyed, or even have a perspective from which it's possible to appreciate them. This despite the fact that Bosch anticipated misunderstandings, and took great care to build multiple visual keys into his paintings to indicate his intentions. Having published this work in various forms over the past three years on the web, one of my friends asked me to pull it together into a book. This, then, insh'Allah, will be the result; Amen. Lee van Laer, July 2013

Lee van Laer |

||